The Work of Li-lan: Postcards from the Edge

Scarlet Cheng

Asia Times

October 1996

New York-based painter Li-lan is surrounded by hyphens. The one in her name is the most obvious and the one between “Chinese” and “American” is the next. And then there are those unseen hyphens – between East and West, between continents and cultures, between left and right brain, between the chaos of human experience and the order that she tries to impose on to her spare, Minimalist canvases.

Her latest work, which opened at the New York’s Art Projects International Gallery on October 24, reveals a new spirit in both execution and conception. As always, the painting remains meticulous, but now it feels freer and less overworked.

The subject matter is also familiar and distinctly Li-lan. As before, she takes elements of envelopes, postcards and postage stamps, adds and substracts details according to her intuition, and renders her vision onto large linen canvases. But now she is adding more pictorial elements into her work and forcing her compositions into tilts, veering away from the frontal and rather static nature of her previous pictures.

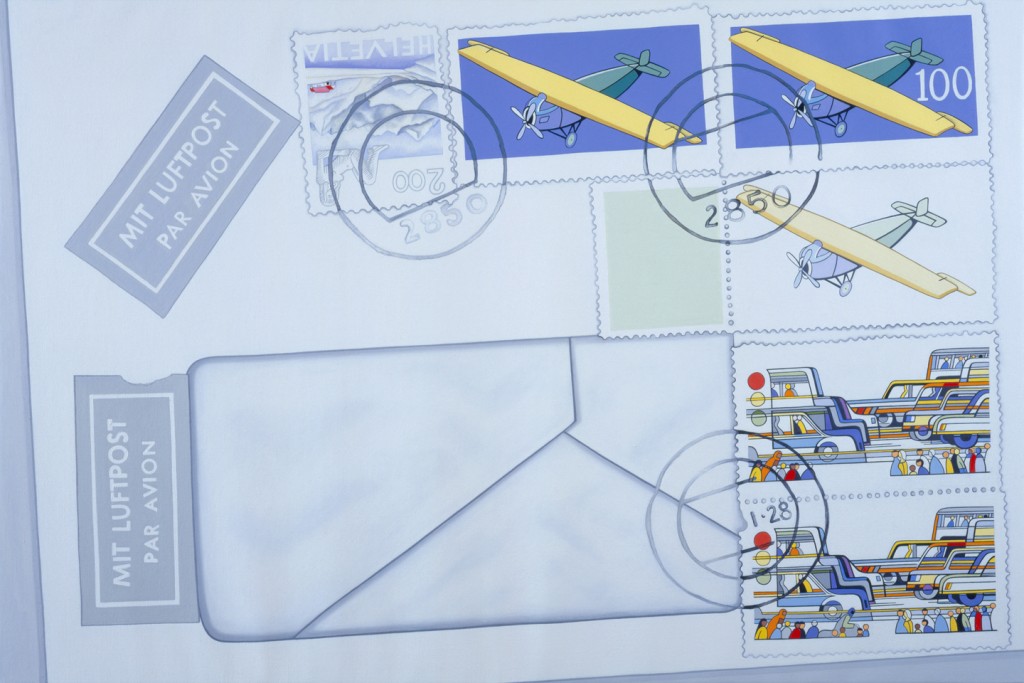

Mit Luftpost, Par Avion, 1995

Mit Luftpost, Par Avion, 1995

Many of her works also show multiple perspectives. In Both sides of a Card and China: Two Cards, Two Sides, we see the front and back of postcards. In Mit Luftpost we see the front of an envelope plus some of its inside flaps through the glazed window. Often there is gentle irony in these works, and the latter is no exception. Mit Luftpost means “by airmail” and the envelope is decorated by three stamps of single-propeller planes, as well as two other stamps of cars stuck in what looks suspiciously like a major traffic jam. So, flight, and all its implications, is contrasted to getting hopelessly stuck en route to somewhere.

A lot of thought goes into these compositions and Li-lan often studies her collection of actual stamps, postmarks and envelopes. “I have file boxes full of stuff, ” she explained. “Sometimes I remember things that I want, sometimes I leave them out on my desk when I want to use them.” But the final product, she insisted, is intuitive, rather than reasoned out. “Nothing gets done right away,” she said. “Everything gets subliminally done many times before it gets put onto the canvas.”

Born and raised in Manhattan, Li-lan grew up under the influence of art. Her father was Yun Gee, who left China in 1921 to pursue the heady career of a young artist in Europe and the United States. Settling eventually in New York, Yun Gee married an Austrian-American, but they divorced when Li-lan, their only child, was two.

On weekends she would visit her father at his Greenwich Village studio and she was introduced to art exercises with pencil and paint. Today he is considered a leading, if somewhat obscure, modernist painter of the 1920s and 30s, and his works hang in the permanent collections of such institutions as the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington. As caretaker of her father’s works, she generously lent many of them to the major Yun Gee retrospective at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in 1992.

At first, Li-lan considered an acting career and attended the High School of Performing Arts in New York – the school made famous by the movie Fame But then, she said: “While studying acting, I realized that it really wasn’t the vocation for me. In a way I prefer solitary work and somehow painting or writing seems more like me.”

In the late 1960s, she met Japanese printmaker Masuo Ikeda and they got married in 1969. That year, at the age of 26, Li-lan had her first solo art show at the Miyuki Gallery in Tokyo. For the next 12 years, she and her husband led a multi-continental existence in the United States, Europe and Japan. For her, going to Japan was like a homecoming. She had long been drawn to Japanese culture, ever since working for the Takshimaya Department Store in New York in 1960. “I was very attracted to the Japanese culture right away,” she recalled. “I wanted to go to Japan and I started studying Japanese.”

After she and her husband separated, she returned to New York to live. Now she feels this is where she belongs. She works most of the year in Manhattan with summers and some weekends at a quiet retreat in East Hampton, a couple of hours drive from the city.

“In the US I would always live in or near New York, but I always wanted to be connected up with Asia somehow,” she noted. Although she grew up in a Western-educated society and with a very Western mother, she has always felt a pull toward Asia and Asian culture. She has twice visited her father’s village in Guangzhou. “I don’t know if it’s accidental or deliberate, but I’ve always had a connection to Asia,” she said. “In some ways, it comes from a longing or yearning for that side of myself.” This morning in her spacious Canal Street studio in lower Manhattan, Li-lan puts the finishing touches on a painting propped against the wall. Light streams in from a bank of windows which affords a vista of the Hudson River.

“Sorry for the mess,” she said with a small laugh, surrounded as she is by art supplies and half a dozen finished and nearly finished canvases.

For someone habitually ordered and neat, this spillage of creativity just before the show she is preparing for is something to apologize fore. Yet the “mess” is not chaotic. She knows exactly where everything is, the dozens of brushes are held in ceramic pots on the taboret, and the paints are contained in jars and tubes gathered on the floor by the latest painting – a painting which depicts two Danish stamps canceled on the diagonal, a bar code, plus the overlap of what looks like the back of a blank postcard. The paints are on the floor because she works sitting on a wicker picnic basket. “I like to be close to the floor when I’m working,” she said.

While at first the outlines of her objects seem drawn in, she actually creates their edge by painstakingly reducing the line by filling in the white or background areas around it. To give depth to the color, she applies the background in layers, often using four or five coats for the right effect.

Both Sides of a Card, 1996

Though some prints and pastels will be available at her upcoming show, the centerpiece will be the eight paintings. Both Sides of a Card is one of the most striking of the paintings, showing the pyramids of Giza, stacked like geometrical shapes, one behind the other. Here she shows the arrangement twice from two different perspectives. First on the left on a postage stamp stuck on a postcard, then again on the right which is presumably a section of the front showing the pyramids in an enlarged version.

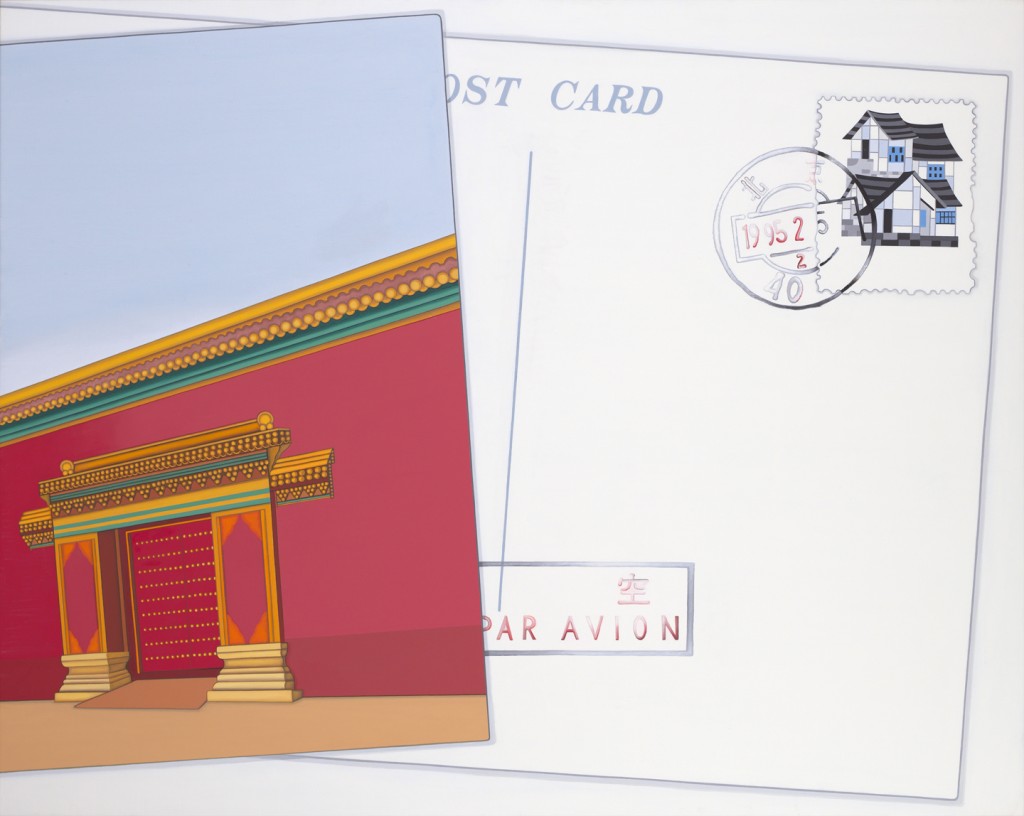

China: Two Cards, Two Sides, 1995

At an impressive 127cm x 165cm in size, this work is both a peaceful meditation of earthen tones braced against the white space of the postcard, as well as a dynamic composition of diagonal lines and triangular spaces. These days there are always some Asian touches. In China: Two Cards, Two Sides, she again shows two sides of a postcard – a shut vermilion door from the Forbidden City overlaps the back of a postcard with one canceled stamp on the upper right hand corner.

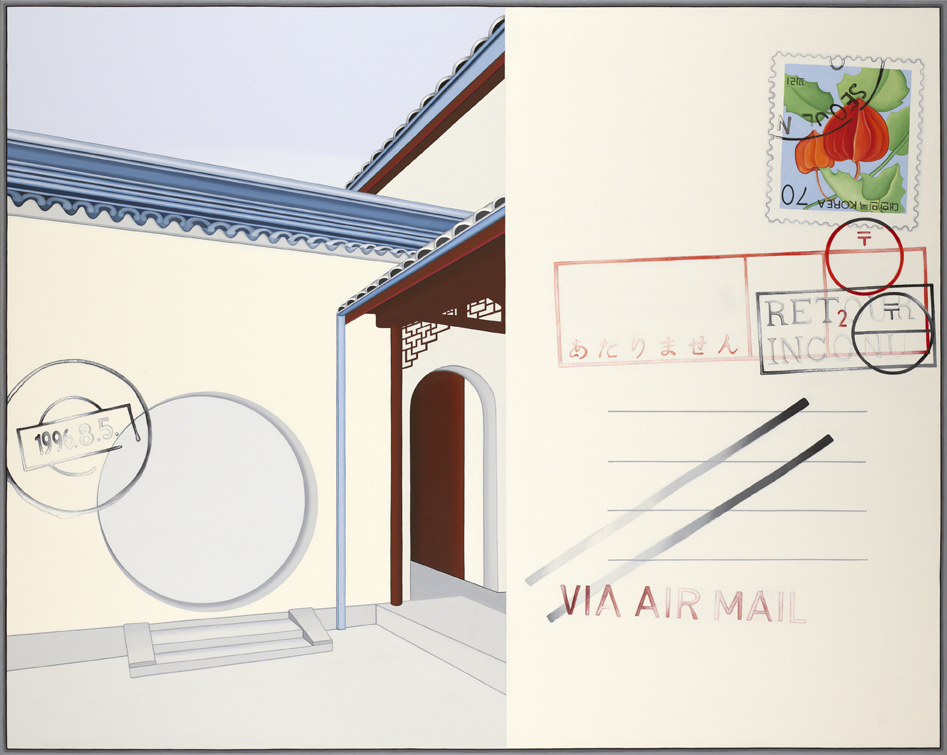

Correspondence East, 1996

This stamp shows a stack of Chinese cottages, as humble and plain as the Forbidden City gate is imposing and formal. Correspondence East shows an architectural section of a Chinese-style garden – including a moon gate – juxtaposed with a Korean postcard which has apparently been returned due to an unknown address.

Transnational and multicultural, caught up on journeys between countries and borders, these works reflect a kind of thought diary for Li-lan. “Even through my works are kind of cool and detached,” she admits, “they also have my autobiography in them. When I’m painting I’m always thinking of things and interjecting them in one way or another.

SCARLET CHENG writes regularly about film and the visual arts, and has been published in the Los Angeles Times, ArtNews, Art & Auction, and Vogue. She has been a writer and editor at Time-Life Books in Alexandria, VA, and the managing editor of Asian Art News magazine in Hong Kong. Currently, she also teaches at Otis College of Art & Design and Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles.