Li-lan, Stationary Images

Robert Berlind

LI-LAN, Stationary Images: Paintings and Drawings, 1982 – 1990

(The William Benton Museum of Art Exhibition catalogue)

November 1990

Robert Berlind: Your early work was filled with imagery from the Italian Renaissance and was cryptic, with personal signs and figures. Could you talk about what motivated you to let go of that imagery?

Li-lan: In the middle 60s I spent time in Italy. I loved the frescos of Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Masaccio, and Fra Angelico. I incorporated images from these artists into my paintings in a collage or montage-like way. In some I combined the Florentine portraits – profiles and silhouettes – with other elements I was using then, such as doors, windows, chairs, apples, eggs, and running Muybridge figures.

One day – it must have been in the early 70s – I was sitting in my studio in East Hampton, a sketchbook on my lap. I was emptying out my mind, thinking about what I was going to draw or paint. At that moment I wanted to paint the sketchbook, so the sketchbook moved from my lap into a painting. At first I combined sketchbooks and notebooks with the other images. Over time the notebooks themselves, or blank pages from them, grew larger and larger, and the other objects, such as the cups and nails, began to disappear, or leave one by one. It was an emptying out process. As the notebooks and blank pages grew larger and larger – larger than life – my paintings became more minimal and solitary. The images themselves had always been isolated from one another to create a sense of aloneness, and as time went on each image began to stand alone on the canvas.

My Sketchbook – 1974

My Sketchbook – 1974

Robert Berlind: It’s almost as though your interest in the Renaissance went from the images and the figures and the stories to the grid, which is also a Renaissance invention.

Li-lan: Right. That’s right. I have used the verticals and horizontals of the grid to create a formal tension in my composition and a feeling of harmony. I have also used it as a means of working with the repetitive image and with the opposites of stillness and movement.

Robert Berlind: What was your relation to the work of that time, to the work of Minimalists like Sol LeWitt or Agnes Martin?

Li-lan: I admired and felt an affinity with both artists. When I started painting my large legal pads and books without words, I wasn’t aware of Agnes Martin’s work. People who saw my work suggested a relationship. There is a warmth and intimacy in Agnes Martin’s paintings that is not mechanical but of the hand. I find this same feeling in Mondrian. His paintings have a purity and restraint, yet are very much of the heart and hand.

In my paintings, I am also very concerned with their surface and with the quality of the materials used. I don’t spray, use tape or stencils. I build up my surface with several layers of oil paint so that the flat areas have a richness. I even paint each line several times to create a slight texture. If you look closely, my lines are not quite even but a bit wavy, the rows of dots not quite straight or of uniform size. Although at first glance my work appears to be very precise, in actuality it is not. I am interested in the play between the mechanical and the handcrafted.

Robert Berlind: The other group of artists that need to be mentioned in this context would be the Pop artists who appropriate a mechanically reproduced image. Lichtenstein took the comic book image and made it the painting, co-extensive with the canvas. In a sense you’ve done that with the various printed forms you were using at that time.

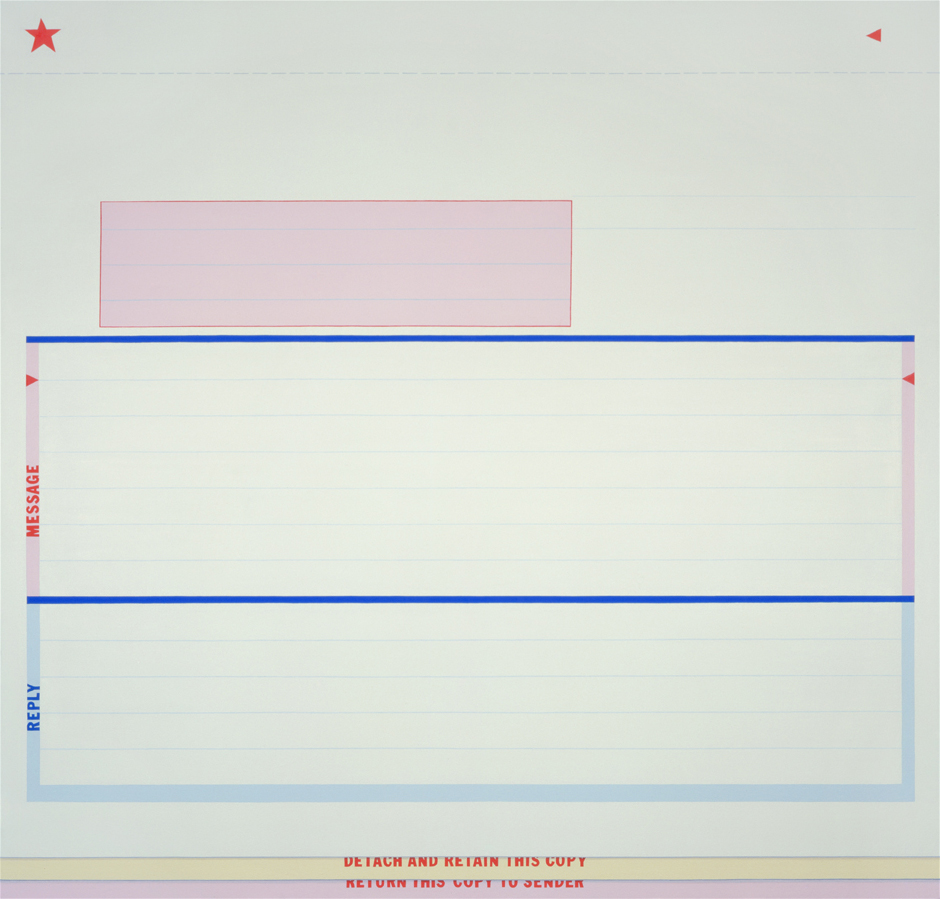

Li-lan: Yes, I did. In the 80s the large-scale sheets of blank or ruled paper I was painting began to change into printed forms like sales-books, checks, computer forms, invoices, and so on. The paintings became like the objects, greatly enlarged. These are the images that would appear more Pop-like, although I was not consciously thinking Pop art when I started this series. Rather it grew out of previous work.

On the other hand, my process of paintings is my own. I look at the model I am using. I put it down on the floor next to me. For me, it is both there and not there. Sometimes I refer to it, sometimes I don’t. I play with its form on the canvas. I remove or change symbols that are on the actual form. I add arrows or numbers, paint in shadows where there are none. I sneak in elements, perhaps play with numbers that have a personal meaning to me. I change colors. The image may look like the real thing, but it is not, and this internal drama is a hidden part of the painting.

Robert Berlind: So the process, then, is really very important to how the work finally presents itself. Sol le Witt explicitly stated that what is important to him is the concept; that anybody can execute it. In fact, he generally has other people execute his work, so that concept and process are separate and distinct. It’s an aesthetic that you do not identify with then?

Li-lan: I don’t. In my work I don’t make a distinction between concept and execution. The process and the act of painting itself are an integral part of my work. In fact, I enjoy painting tremendously – both the physical act of painting and the joy that comes from being a part of the process that takes place as images emerge and develop. Sometimes I work from a thumbnail sketch and change the image as I go along. Sometimes I work from a more detailed drawing. But, either way, I like to let some things happen spontaneously on the canvas.

Robert Berlind: You’re using those printed forms and sheets of paper, but there is still an element of the unconscious operating.

Li-lan: That’s right.

Robert Berlind: And you don’t have to emphasize that “element of the unconscious” very much if the foil is the printed forms, something that’s absolutely mechanical. The subtlest variation of an edge or a slight shift in color is sufficient to arouse another kind of feeling.

You spoke a moment ago about emptying your mind while painting. That suggests a Zen attitude, a kind of clearing away of distraction. And there is that wonderful statement that Noguchi made about your paintings:

Li-lan has found that blank page of our school notebook which we may all claim as our own. Upon it we can write our thoughts feely, beyond race and without prejudice.

Li-lan: Exactly. There is an empty space, a place for thoughtfulness and introspection, quiet and solitude. There is a moment of stillness, of cessation of thought.

Robert Berlind: That’s really quite distinct from New York art of the formal persuasion that relates to your work. You know, that kind of hard-headedness, that analytical toughness of Minimalist art. Like Agnes Martin, you depart from that aspect of Minimalism and open up other kinds of possibilities, although you use some of the same forms. On the other hand, your works that are based on order forms, delivery forms, and other low-end technological kinds of messages are parallel to the kind of appropriations that Warhol made when he deliberately did not choose elegant advertising. He chose things like the ads in the back of the newspaper for aluminum windows, and matchbook ads for getting your nose fixed. In a way, there could seem to be an extreme irony in your choosing that sort of low-end stationery.

Li-lan: It’s humorous – or ironic – to enlarge a mundane, mass-produced piece of printed material and transform it into a sensual icon for contemplation. Especially since I choose the most ordinary, most unartistic and prosaic subject matter.

Robert Berlind: And yet in your making of those paintings, there’s this hint of everything that’s opposite from the mundane and prosaic. A particular kind of light is given off by the interplay of your pinks and yellows that is not to be found in those stationery forms. And with that, qualities of emotional nuance that are anything but prosaic.

Were those forms something that you simply discovered and then found that they clicked?

Li-lan: Yes. There was a natural progression from the legal and memo pads to the accounting books, to these prosaic forms. I do remember sitting at my desk one day looking at a pile of checks, receipts, invoices, and saying why not. So I began using them as subject matter while keeping the same concerns with paint surface, light, and clarity, for example, that I had always had. I also added additional, rubber stamp-like messages: Paid, Billed, Approve, Reject. Both the stamped words and the forms are very much a part of my daily life. A landscape of our modern world, so to speak. And on these forms come many commands: Press Hard, Detach, Retain, Return to Sender. Do this and don’t do that. I love to look at them; I think they are very funny. As you said, this hint of everything that’s opposite is one of my key concerns – the tension set up by intuition and control.

2 Way Reply Message – 1985

2 Way Reply Message – 1985

Robert Berlind: Is it fair to say that your choice of subject matter was never part of that Post-modernist argument about originality? The appropriations that you made really were more in the sense of using what was on hand as you happened to notice that notebook and think, here’s a possibility.

Li-lan: That’s right. From the early 60s on, I have incorporated into my paintings objects and ideas from my everyday surroundings that have inspired me. I did so long before doing so called “appropriation,” and although some of my appropriations are of impersonal items, there is something personally significant about them for me, even autobiographical. For example, while in Japan in the 70s, I was writing a book about my life and thoughts that was published there (Canvas With An Unpainted Part, An Autobiography, 1976), and during that time large books without words appeared on my canvases. I am often asked if I choose my material for its purely formal elements, or if there is emotional content in my choices. Both are true, although you may have to read the emotion between the lines, as there is a great deal of understatement, restraint, and concern with formal issues in my work, which is essentially reductive.

Robert Berlind: So it’s not that you are pointedly using something unartistic the way, for example, Warhol was.

Li-lan: Correct.

Robert Berlind: Then in 1986 and 1987, you began to use sheets of stamps, uncut, straight from the post office in your paintings.

Li-lan: Yes. In 86 I began doing drawings of stamps and in 87, paintings. At first I painted whole sheets of 40, 50, or 100 stamps, or fewer if from a torn sheet. What initially intrigued me were not the stamps but the printer’s color-separation key, which is on the edge of the sheet of stamps. In fact, I had torn a color key off one and had it on my desk for several months before using it. When I did paint it, I placed it at the bottom of 100 “Orchids Issue” stamps. I was also intrigued by the grid layout of the sheets and its regular perforations. (So far, I must have painted thousands and thousands of dots by hand in this series.)

In the stamp paintings, I am able to explore even further what I was doing with the stationery. There is a lot of room to play freely. I paint some of the stamps in their entirety, some only in part; some in their real colors, some in mine. I leave blank – or empty – areas in the stamps for the stamps white. In some of the spaces a simple detail or fragment such as “22” or “25” appears. In others an American flag or the Capitol from the most commonplace of stamps is depicted. I pay attention to what we take for granted or simply overlook. Until I started painting sheets of stamps, I had not noticed the many varieties of color-separation keys found at the edges. Some of the images I use are so familiar that you may not realize how I have changed them. Your mind may automatically fill in the blanks with your own memory or imagination.

Eighty 22’s – 1988

Robert Berlind: Yes, and the stamps also formally complicate the paintings because they are images, and a range of images at different scales. In some of them it’s almost as though you’ve found a way through the back door to deal with landscape, to deal with portraiture, to deal with the figure, to deal with a lot of the subjects of your earlier paintings. The stamp paintings also combine different modes of representing things. That diversity was also part of your earlier work, where things are more or less three-dimensional and more or less expressively drawn. The new work finds a way of recouping some of what you had let go earlier without sacrificing that meditative character.

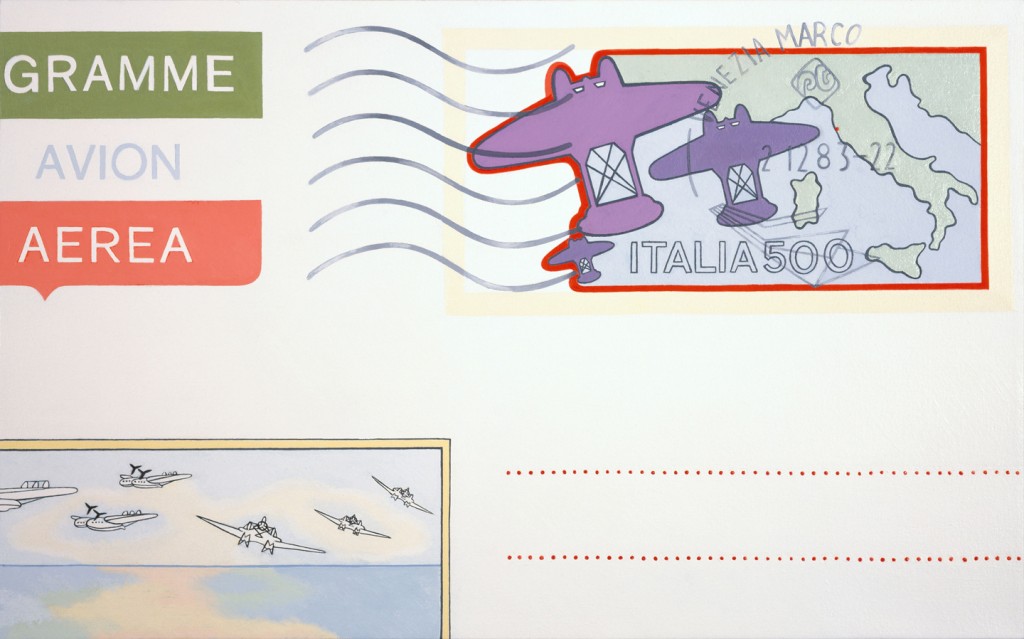

Li-lan: True, and as the sheets of stamps became stamps on envelopes, there was another shift with other levels of meanings. An envelope with stamps on it may be postmarked or it may not. Maybe it’s already come in the mail, maybe it hasn’t. The stamps themselves may conjure up many different associations.

Robert Berlind: That was an extreme jump when you went from the sheets of stamps to the envelope as the image. The game changes quite dramatically. Montefegatesi has the shape of an envelope and slightly irrational postmarks that do not cancel the stamps. More strangely, it doesn’t have an address, and the absence of the address becomes an issue, doesn’t it?

Li-lan: That’s right. What is “absent” or not there is as important to me as what is there. This has continuity with my earlier work in the elimination of information, and my concern with empty space, with the void.

Robert Berlind: But here the absence is part of a story with an irrational element in it: how would this envelope have gotten here? Moreover, letters themselves signify distance because the other person is not here and these are your friends.

Li-lan: Right. I have friends both here and in other countries. I have also traveled to and lived in other parts of the world. I like to stay in touch with people and cultures. The correspondence conjures up a past, present, and future for me. I might write a letter saying “hello” and a year later receive an answer. This form of communication has something to do with being alone yet being in touch with the other.

Some of the envelopes I paint have been sent to me, but some of them may have been sent elsewhere. Friends now collect and give me envelopes, or I happen on stamps or envelopes by chance. I keep them because I never know which one will become a painting until I begin it. As in my earlier work, I combine parts and fragments of different envelopes as if creating a collage: a stamp from this one, a cancellation from that one.

Robert Berlind: You said earlier that you spend a lot of time either at the easel or at your desk.

Li-lan: Yes.

Robert Berlind: Your desk is the place where you do the letter writing and reading and where you have that connection with the outside, and the easel is where you have your meditative space. So the envelope paintings show both aspects of your studio world: desk and easel. The stamps on the envelope paintings also bring back the stamp-page imagery, and when the stamps refer to Italy they bring back the Italian Renaissance as a subject from your earlier work. So, a major theme of the envelope paintings is longing, distance, absence, with the surrealist overtones of the empty envelope.

Li-lan: I have always loved the Surrealists, and I do relate to the feelings of absence and solitude that I find in Surrealism.

Robert Berlind: There’s a difference, though. Most Surrealists art has a loaded content that is either about anxiety and/or sexuality and/or violence and/or flights of fancy into extreme places. Your work really never departs from a certain kind of calm, an encompassing quality. Your work remains very centered emotionally. It’s very quieting.

Li-lan: I think that the act of painting is what centers me, because I am not really as calm as I may appear. When I am sitting alone in my studio and thinking or working, that is when I can achieve calmness or serenity. Our daily lives are full of anxiety and problems, and sometimes I think I am looking for that quiet space where I feel centered and at peace. Maybe I’m looking for the place which doesn’t really exist in the real world, but . . .

Robert Berlind: That is the role of your art, isn’t it?

Li-lan: Yes, a place where I find my moment of quiet, brief though it may be.

Robert Berlind: There is another formal element in your paintings that I want you to comment on. It’s what goes on at the edges.

Li-lan: In some paintings, the bar code, color chart, or words at the edge of a page call attention to the edge of the canvas as if the image is the object itself. These peripheral elements are also indicative of the printing process, of the reproduction of an object. In some works, I have framed the image with a painted frame or a thin strip of background, which also defines the edge of the canvas.

Robert Berlind: Perhaps, in a subtle way, this goes back to the Minimalist idea of the work acknowledging its physical character.

Li-lan: Yes, that’s true.

You know, people always ask me where I get my images from. I can’t tell you why some objects and ideas appeal to me as subject matter and others don’t. My images evolve naturally. I enjoy letting images emerge without too much planning or premeditating. That way I surprise myself. For instance, I will find a stamp, envelope, whatever interests me. It will sit on my drawing table for a while. It is in the back of my mind. Then one day it becomes part of a painting. In the same way, I discard images that I was certain I would use. The elements of chance as well as intuition are at play. It feels as though the subjects choose me rather than me choosing the subject.

Robert Berlind: Something has just occurred to me. Maybe as an artist one is least deliberate where people think you are being most deliberate – in the choice of subject. And where one is really deliberate – in terms of the approach to that subject which you carry with you from one painting to the next – it is precisely that thing that people don’t’ see.

Li-lan: To allow chance may also be deliberate. Then everything depends on noticing what’s happening and the quality of noticing is what becomes crucially important.

Robert Berlind: Well, the paintings certainly attuned the viewer to that quality of noticing. In order to see them at all, one has to slow down a little bit, become receptive, and start to move into that space. With respect to that quality, however, the direction that you move into with the envelopes, which have so much more information, leads you into areas that are more refractory and more difficult to control. When I see the painting rue du Dragon, I think, “I know that street, I had a friend who lived there, I know a restaurant there,” and suddenly I get very particular in my thoughts and less contemplative. So the more information, in a sense, the less contemplative our response, but then, one doesn’t always want to be contemplative.

Li-lan: Right, that’s true.

Robert Berlind: So maybe that represents a kind of opening into more particular experiences that are less centered because they engage the world in more specific ways. And looking at the early work, I would say that also.

Aerogramme – 1990

Li-lan: When I look at my work from the 60s to the present, I find that some of my concerns or ways of working remain the same although they may appear in different forms. I didn’t plan for them to be the same; I guess it’s just an expression of who I am. Some things remain the same, and some are moving and changing, evolving. The stamp series has been changing as I go along. It started with the sheets, moved on to stamps juxtaposed with other elements, such as the Photostat scales in Mocambique, turned into envelopes as in Montefegatesi, and fragments of envelopes in Aerogramme. The latest painting in this exhibition, The People’s Republique: 50 Yuan, is from a detail of an envelope that relatives of mine sent to me. They live in the house that my father was born in, in a tiny agricultural village in Kwangtun Province. I met my relatives for the first and only time in 1980. So this letter is very meaningful for me. The stylized army tractors coming down a mountain in winter next to a stamp of a flower in full bloom struck me as ironic. The postmark on this envelope is rather messy and streaky. The postmarks in my most recent work are taking on a life of their own – freely moving around the canvas in various shapes, shades, and rhythms. I do not know what will happen next with the envelopes, but I am having a lot of fun with them.

Robert Berlind: There won’t be addresses on them?

Li-lan: Addresses, but only partial addresses, are beginning to appear on some of them. I don’t know if I want to give too much information away.

Robert Berlind: But we’re definitely not going to get the letters.

Li-lan: Maybe I’ll send the paintings through the mail, and see what the Post Office does with them.

Robert Berlind: The letter itself is a kind of metaphor for the artwork, isn’t it? You put something together and send it out from the studio and the viewers receive it, if they receive it. Some letters go astray, some get re-routed. Paintings and letters pass through hands that are either that of the post office or a critic, and somebody receives something a little bit altered.

Li-lan: Right. Or it comes back to you “return to sender,” or the person has moved, or the person has died, or the person . . . you know, all of those things that happen in our lives and other people’s lives.

Robert Berlind: Or they all go to the proper address and are seen at once. Perhaps somebody has been saving them. That’s called a retrospective.

Li-lan: Yes, that’s good.