From China – 1992

New York-based painter Li-lan lives on two hyphens – the one in her name, the one between “Chinese” and “American.” And then there are the unseen hyphens – the one between the left-brain and right-brain, between the chaos that is human existence and the order that her spare, Minimalist art tries to attain.

This coming May, her works, which have been long exhibited in the United States and Japan, will arrive in Taiwan. Lung Men Art Gallery, Taipei, will be featuring 12 of her oil paintings and six drawings in a solo show called Correspondence: Between the Lines, Taipei.

Twice I have met the artist. The first time in Washington, D.C., in 1989, when she had a show at one of the city’s top galleries, Franz Bader, run by the energetic Wretha Hanson. And last fall when se came to Hong Kong to attend Art Asia.

Soft-spoken, with medium-length, frizzy hair, Li-lan strikes one as being imminently approachable. She talks about herself and her art thoughtfully, avoiding the jargon and the jive of some too-too hip New York artists. But beneath the unpretentious modesty lies a singular determination and belief in her own work – and the process of her work.

Born and raised in Manhattan, Li-lan was under the influence of art early in her life. Her father was Yun Gee, who left China in 1921 to pursue the heady career of an artist in Europe and the United States. Today he is considered a leading, if somewhat obscure, modernist painter of the 1920s and 1930s, and his works are in the permanent collections of such renown institutions as the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. (As caretaker of many of her father’s works, Li-lan was instrumental in arranging the major Yun Gee retrospective at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in 1992.)

Li-lan grew up in a turbulent household, and her parents divorced when she was two. On the weekends she would regularly visit her father at his Greenwich Village studio. There, Yun Gee would put his young daughter to work, giving her art exercises to do with pencil of paint.

Originally, she had felt a call towards an acting career. She managed to enter the prestigious High School of Performing Arts in New York – the school made famous in the movie Fame. But then, as she tells me in a recent telephone interview, “While studying acting, I realized that it really wasn’t the vocation for me. In a way I prefer solitary work, and somehow painting or writing seems much more like me.”

As soon as she graduated, she bravely moved out of her mother’s household and got a loft on her own. She explored various art styles, hired herself a weekly tutor, and hung out with other artists. To pay the bills, she took on a variety of jobs – including waitressing, design, photography, and even writing. For a while, she and a friend had a thriving business making antiqued wood panels from pieces of wood found abandoned on the streets of New York. These reproductions of primitive early American art, Russian icons, and the like were successfully sold to stores around the city.

In the mid 1960’s she met the Japanese printmaker Masuo Ikeda. They married in 1969. That same year, Li-lan had her first solo show – at the Miyuki Gallery in Tokyo. For a dozen years, she and her husband enjoyed a multi-continental existence in the United States, Europe, and Japan.

Going to Japan was like a homecoming – she had long been drawn to Japanese culture. Even in 1960, she recalls, when she worked at Takashimaya department store in New York, “I was very attracted to the Japanese culture right away. I wanted to go to Japan, and I started studying Japanese, and reading, and trying to figure out how to go there. During that period, I met people who were very key in my life, like Isamu Noguchi.” It was Noguchi who once wrote, “Li-lan belongs in the same way as I do to that increasing number of not exactly belonging people.”

And when she finally arrived in Japan, her affinity for Japanese aesthetics was confirmed. To this day it continues to be reflected in the strong use of negative space that persists in her artwork.

Eventually she and her husband separated, and Li-lan returned to New York to live. Nowadays she splits her time between her apartment/studio in Manhattan and a quiet place out by the ocean in East Hampton, a couple of hours by train from the city.

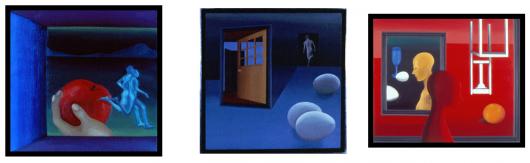

Li-lan once tried Abstract Expressionism, but she felt that it did not suit her. “I’m too neat and precise a person to paint that way, ” she has said. Instead, some of her earlier paintings show a fascination with surrealism, as well as an admiration for the early Renaissance.

Tuesday Landscape Green (left) Passing Night(center) Between Monday Morning and Saturday Night (right)

Tuesday Landscape Green (left) Passing Night(center) Between Monday Morning and Saturday Night (right)

Her 1971 show at Nantenshi Gallery in Tokyo included graphic and mysterious paintings of rooms within rooms, doors opening onto doors, running men, giant eggs, Renaissance ladies holding apples in hand. The titles such as Tuesday Landscape Green, Passing Night, and Between Monday Morning and Saturday Nightreveal a preoccupation wit the passage of time.

Soon afterwards, she began painting highly composed still-lifes of open notebooks with a few simple objects – eggs (again!), nails, shadows.

Two Yellow Sketchbooks – 1973

“Then the notebooks themselves began to take over,” she says wryly. “Something about the empty, quite white of the notebooks really fascinated me. It also had a fearful or anxious element. On one hand you’d like to retain the empty space, bot on the other hand you’d like to fill it up!” She laughs. “It’s like before you paint something or write something – there are all these feelings of both anticipation and anxiety. So that’s how it began.”

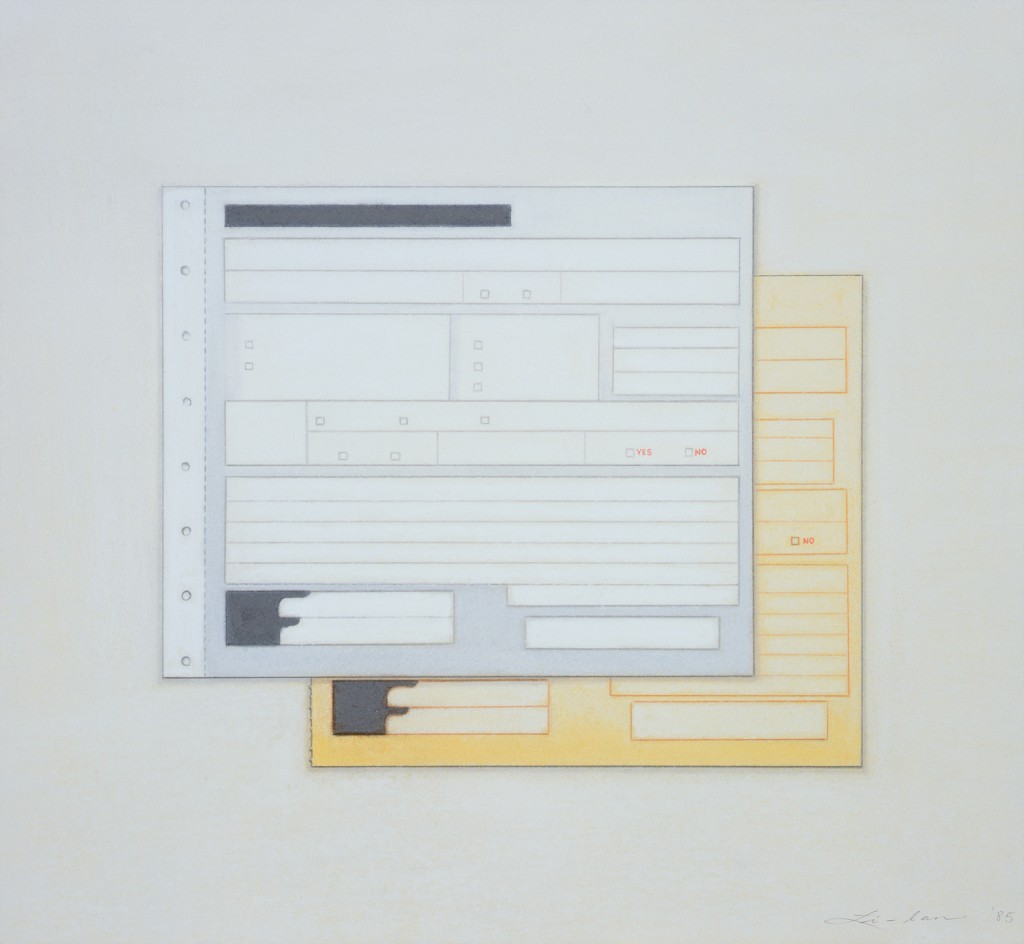

Yes/No – 1985

The notebooks and sketchbooks turned into sheets of paper, then became salesbooks, checks, invoices, accounting books. In 1986 she started painting postage stamps. “One day my eye fell on that little printer’s color key on the bottom of a sheet of postage stamps,” she has said. “I kept that on my desk for several months. Then I did a painting of a sheet of 100 stamps.” Eventually, perhaps inevitably, she moved into stamped envelopes.

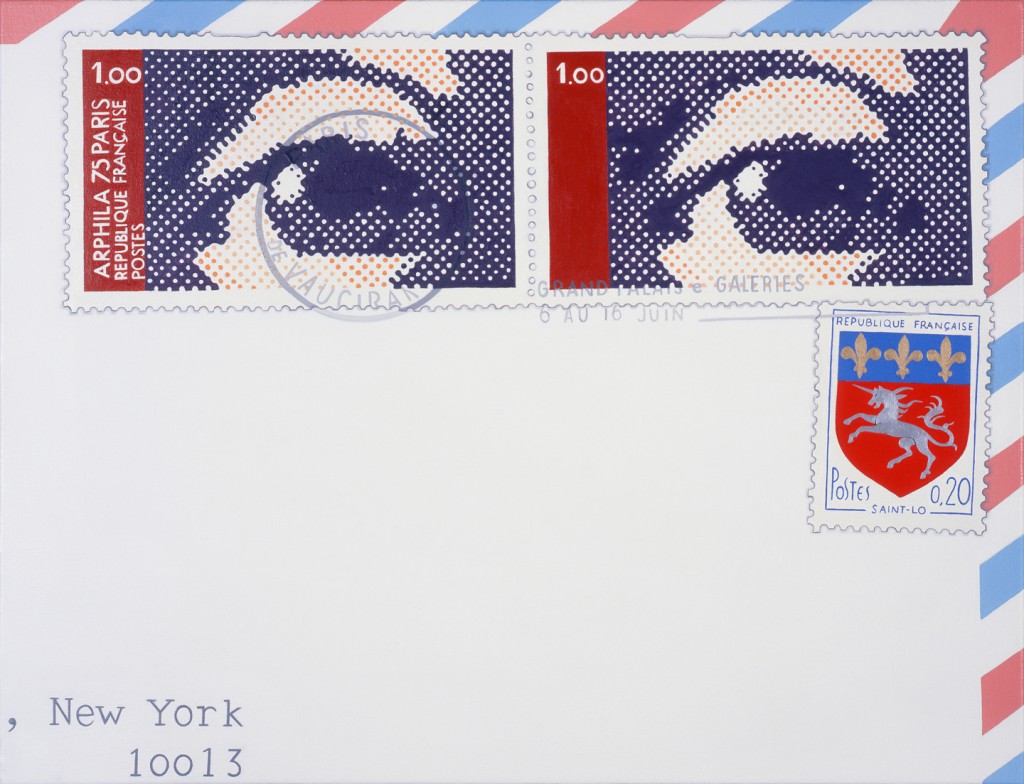

These greatly enlarged envelopes are what she mostly does now. The envelopes bear postage stamps, as well as various cancellations, postal marks, and stickers. Rarely do we see handwriting on them, though the addresses may be typed on. To keep the pristine look of these works, Li-lan signs her paintings on the back. “I don’t want to disturb the image,” she explains.

When Robert Berlind interviewed her in 1990, he noted, “The letter itself is a kind of metaphor for the artwork, isn’t it? You put something together and send it out from the studio and viewers receive it, if they receive it. Some letters go astray, some get re-routed. Paintings and letters pass through hands that are either that of the post office or a critic, and somebody receives something a little bit altered.”

Postes 0,20 – 1989

For Li-lan, “[My work] brings up so many feelings. It also speaks of the void or emptiness. Formally, it’s a use of the space – it’s a way of controlling the space.” Her specific choice of subject matter – that is, which envelope, what stamp gets depicted – is partly accidental. “Since I’ve lived in a lot of different countries, and I have friends all over the world, I have a terrific correspondence with people all the time. So it happens that there are many stamps and envelopes in my house.” She laughs. “And now that people see what I’m doing, they send me their envelopes, too!”

She shifts through these to make her selections. “I never do them straight,” she says. “I generally make a collage of things. It’s like composing a still life.”

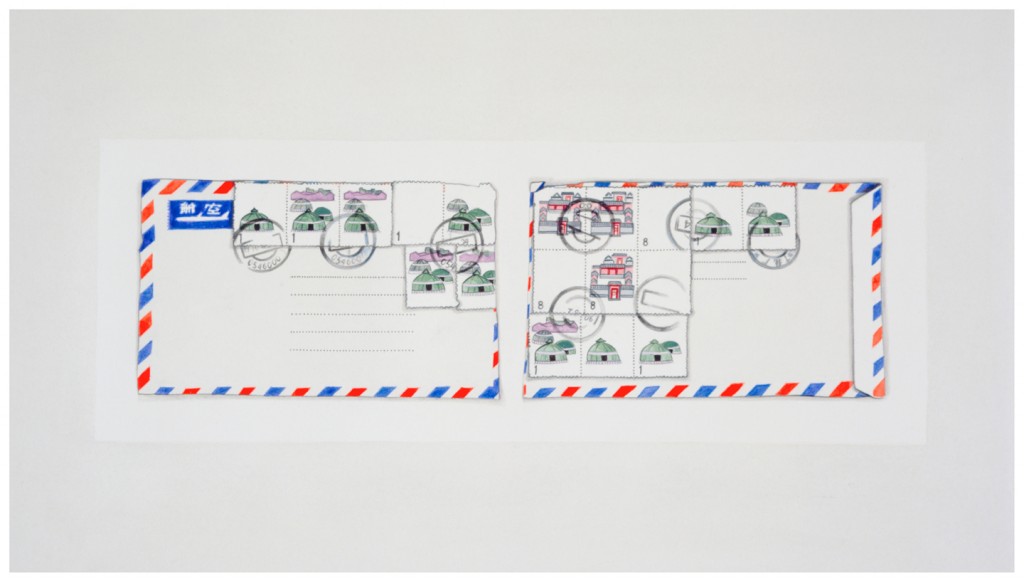

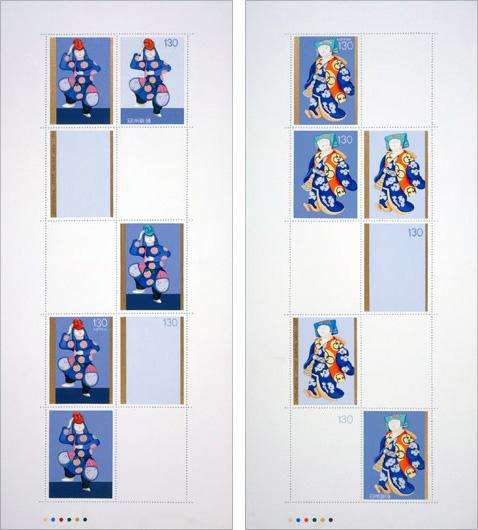

International Letter Writing Week, 1, 1987

International Letter Writing Week, 2, 1987

Even in depicting a sheet of stamps, for example, Li-lan makes her editing. International Letter Writing Week, 1, for example, shows a sheet of ten colorful Japanese stamps, but three of the panels are blank, and the other seven printed are all lacking one of more elements of the missing “whole” stamp. This reminds me of those pairs of drawings in children’s magazines where you are to pick out the errors in Illustration B according to the correct Illustration A. Only in this case, one realizes that something is wrong with all the pictures.

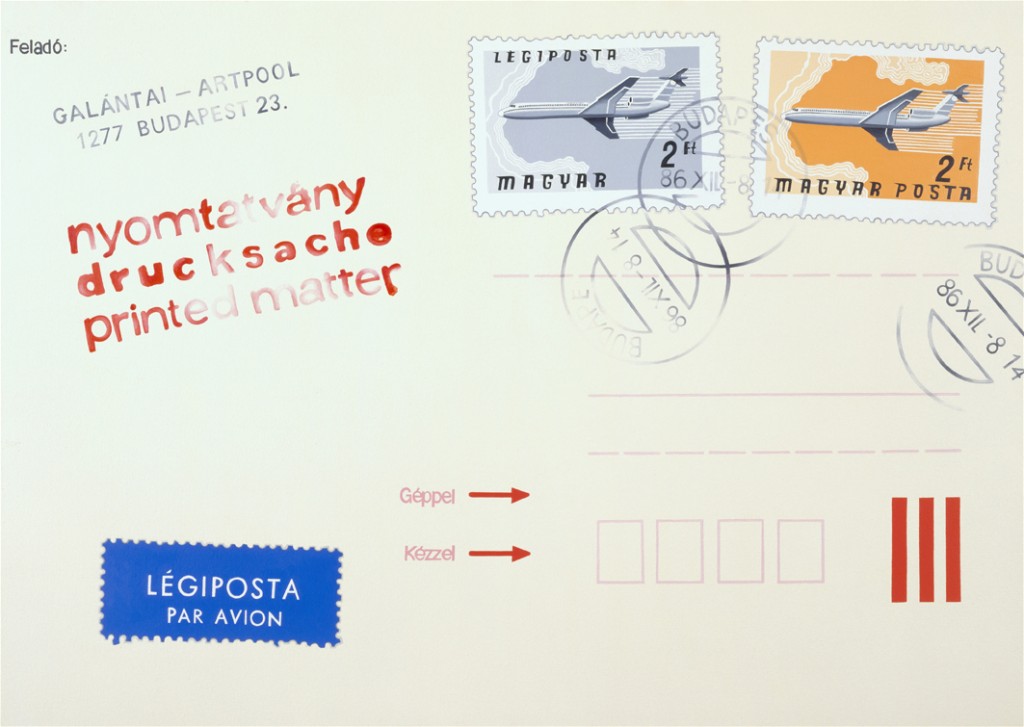

Artpool – 1990

In Artpool, depicting a postal card from Hungary, she shows her fascination with the various stamps that pockmark the surface of a missive. There is the rubber stamp giving the return address of Artpool (some art organization?), the rubber stamp indicating “printed matter” in both Hungarian and English, the blue label designating “par avion” in Hungarian and French, and, of course, the cancellation stamps that smack across the face of the postage stamps. Meanwhile, the stamps themselves show airplanes in flight.

One especially amusing composition was actually drawn as is. The People’s Republic: 50 Yuan, on a 20″ x 20″ linen canvas, shows the end of an airmail envelope with two stamps from the People’s Republic of China pasted on it. The one on the left, in austere blue and white, depicts a truck coming down a mountain in the distance; the one on the right is far more cheerful, showing a large red blossom on a tree branch. It is a decidedly jarring juxtaposition of heavy-duty hardware versus ephemeral beauty.

The People’s Republic: 50 Yuan, 1990

Li-lan chuckles when this work is mentioned. “Oh, I actually got that envelope! Relatives in China sent me that one.”

“My work is formalist in the way I approach it, but it’s basically intuitive. And I’m very concerned with the hand quality.” Ironically, despite the fact that her subject matter is mechanically reproduced images and objects, she herself uses no mechanical means in producing her works. Li-lan prefers to draw everything, meticulously, by hand, using no masking tape or projection.

“But even though my works are kind of cool and detached,” she is quick to add, “they also have my autobiography in it. When I’m painting, I’m always thinking of things and interjecting them in one way or another.” And certainly, in a broader sense, once can see how the envelopes are actually the artist herself – well-travelled, multi-cultural, crossing border, with marks and memories of experiences in many countries.

Li-lan prefers to work by daylight and starts painting or drawing shortly after getting up at eight in the morning. In her painting she works her surfaces carefully, with up to five layers built up on them, and sands in between to keep the surfaces smooth.

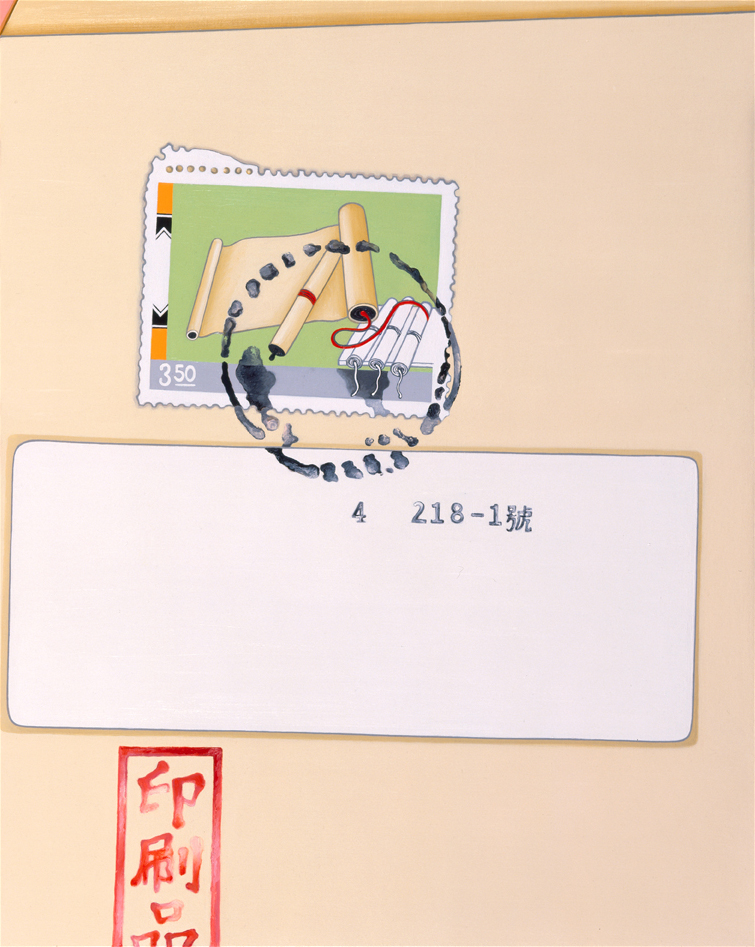

218-1, sec. 4 – 1993

218-1, sec. 4 – 1993

Personally, I find her recent works – which are, in a sense, medium close-ups of the envelopes – more satisfying than the earlier paintings of whole stamp sheets or letters. In selecting and composing her objects more tightly, she helps us to focus in n the subject. Furthermore, partial views are often more intriguing.

Li-lan’s works inspire contemplation, as well as musing. “I think my paintings are a longing for a certain kind of peace,” she says, “I’m looking for that moment of peace – which hardly ever exists in real life.”

Over the years Li-lan has had a stream of shows – from O.K. Harris in New York to Asher/Faure in Los Angeles to Nantenshi in Tokyo. The Lung Men show is her first on Chinese territory and will include a sampling of her small to medium works.

“I’m not sure what people’s reaction will be,” she admits. Having seen last fall’s Art Asia and visited Taiwan, she knows that Minimalism is not “in.” “And yet if I look at the spaces in ink painting, I think the Chinese should be able to relate to my work.”

Li-lan is definitely looking forward to coming east again. Ever since her trip back to her father’s hometown in Kwangtung in 1980, she says, “I’ve been exploring the Chinese part of me – and what I’ve been doing these years has been a continuation of that. I love coming to Asia. Somehow – even though I was brought up by my mother, who was not Chinese – I feel more connected when I’m there, in a very basic way.”

SCARLET CHENG writes regularly about film and the visual arts, and has been published in the Los Angeles Times, ArtNews, Art & Auction, and Vogue. She has been a writer and editor at Time-Life Books in Alexandria, VA, and the managing editor of Asian Art News magazine in Hong Kong. Currently, she also teaches at Otis College of Art & Design and Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles.