Stray Questions, Stray Thoughts (On my exhibit at Nantenshi Gallery in May of 1977)

Li-lan

Ikebana Sogetsu

Tokyo – 1977

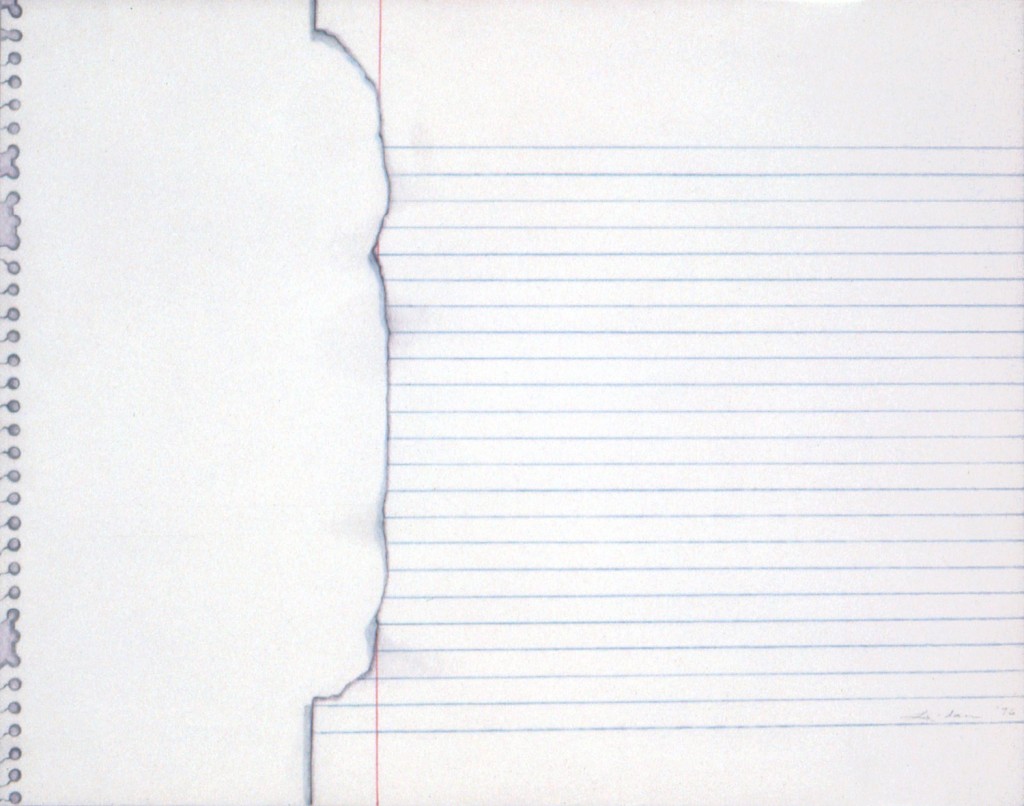

Paper – 1976

Paper – 1976

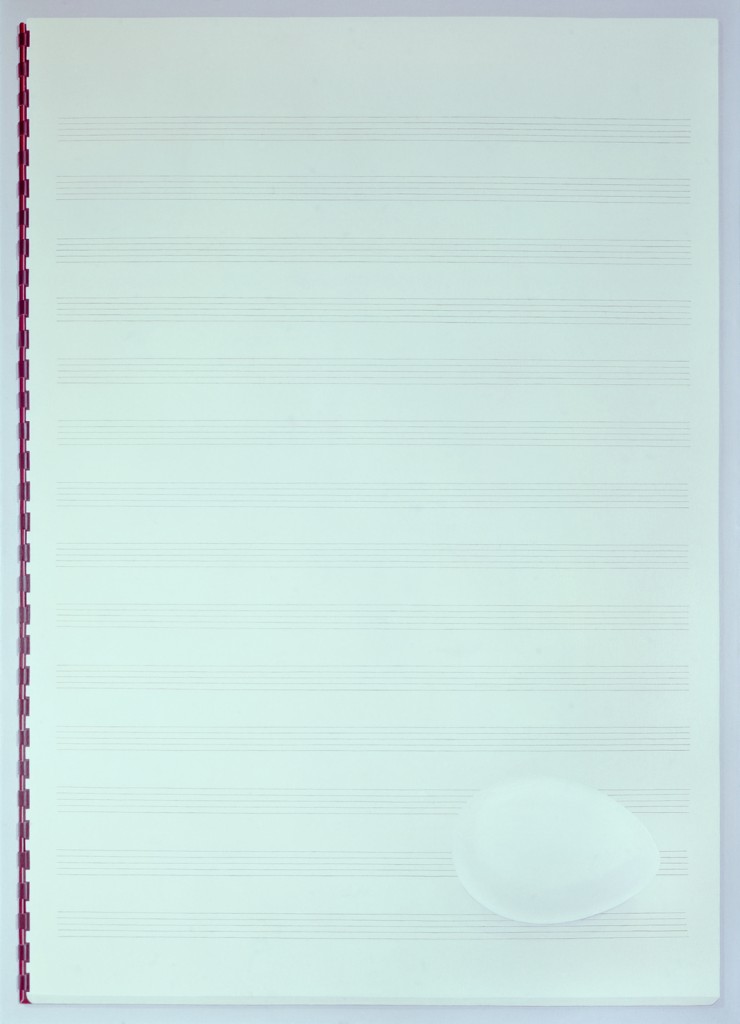

An empty page with its silence, with its yearning, softly whispers to me of the void. In the void there is no time, there is the passing of time – there is tomorrow. Or no tomorrow.

Blank paper, notebooks, sketchbooks, and unwritten books – the void – fascinate, even haunt me. “Why do you paint those images? Eggs? Nails?” People constantly asked me these questions during my recent exhibition at Nantenshi Gallery in Tokyo. Why, I wonder? For I have heard this question many times in New York too. I usually answer, “I don’t really know. The paintings must speak for themselves.”

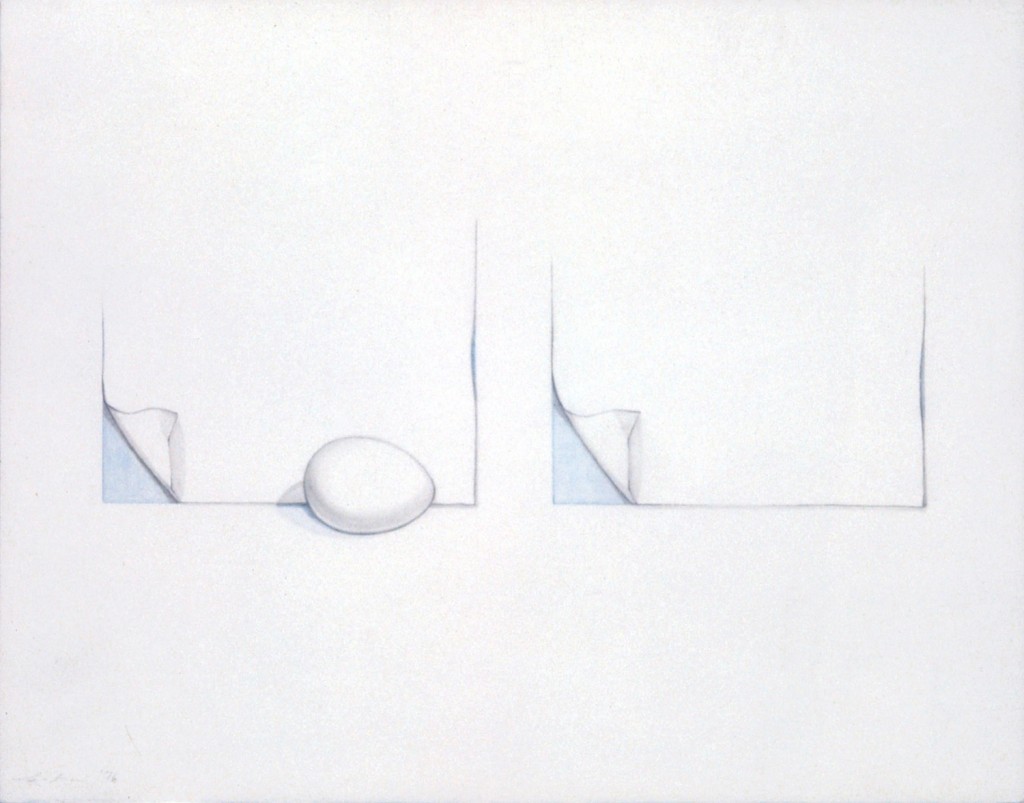

Indeed they must. I could try to analyze, dissect, my subconscious. But even though I have great curiosity, and love to hear others interpretations (always many and varied) of my work, I still have no desire to be too conscious of the sources of my inner symbolism. They are simply reflections of myself. Part of the mystery, and fun, for me, is the way that images surprise me, the way they suddenly appear on the canvas as though they demand to be painted. As though they possess magical qualities of their own. I never know what will happen tomorrow. What will appear or disappear from my canvas.

“Do you have dreams about what you are going to paint?” a Japanese woman writer interested in psychology asked me at Nantenshi as she viewed my work.

“Oh, no. Never.”

“That’s good. I don’t trust artists who say they paint their dreams.” I thought about her comment, for often my dreams are vivid – sometimes too vivid if they happen to be nightmares. I remember colors, feelings, sensations, and situations very well. But, I never dream at night of anything that appears in my paintings. At least as far as I know.

A Peek Behind – 1976

A Peek Behind – 1976

However, I do daydream – play games with myself – while I am painting. I tried to explain that to an editor of an art magazine here, after he asked me, “Do you think while you paint?” I wonder what he thought of my strange description. After I work out the composition, basic idea and structure of the tableau, I play. I fantasize. My mind wanders off into my yesterdays, todays, and tomorrows – like a secret diary. I drift off into my private world of mathematics – for I am always counting spaces; spaces between spaces; lines; holes; nails. Sometimes the objects place themselves in the composition; sometimes my superstitious likes or dislikes of certain numbers help to arrange their patterns. Groupings of certain numbers attract me; others, for mysterious reasons, don’t.

And so, when I am asked, as I constantly am in New York or Tokyo, why I started this series, I mentally run back and forth through my days and nights. But I still don’t know why. I know that it started in East Hampton in 1973 and that it had to do, in some part, with the light.

Until then I had only worked under artificial lights in dark studios, whether in Tokyo or New York. When I first moved to the country in ’72, the brilliance of natural daylight that changes from moment to moment startled me. My bright city colors first turned dark, then darker; then white, then whiter.

At the same time, human figures began walking out of my paintings. Little by little, naked men and women retreated into the background, and paper, or paper like images that had started to appear in the background, gradually became the foreground. At my opening, an American man asked me, “What happened to the humans?” I answered, “Look between the lines, or between the pages. They are hidden, but they are there . . .” The same way I am. Perhaps they are facing solitude, alienation: life.

As the figures disappeared from my paintings, and the paper series appeared, my canvases grew larger and larger. “Why must your paintings be so big?” So many people in Japan asked me this during the exhibition. In Japan, large canvases are troublesome. It’s better to have small objects to tuck away in drawers. Some people, who say they want my paintings, have absolutely nowhere to hang them. I understand that well, for even in my own studio here I have no place for my work. But my images and my natural sense of space dictate their size.

Manuscript Book – 1976

A German woman, who has lived in Japan for many years, mentioned that she was wondering about scale – she felt my sense of space to be very American. I asked her what she meant and she said that although she felt my work to be intiimate, there was still the American spirit of trying to stretch out, expand as much as possible – the feeling that there is some distance between you and the next object. In Japan, one must minimize, as in Bonsai – for in a small room, or in a country with such a great population and so little land, you must immediately contend with the next object, or obstacle.

It must be so, for in America, my paintings don’t seem large at all. Only for me, my large blank pages, my huge white spaces are formidable, frightening. I feel empty; I feel full. Everyone asks why I don’t write words on my painted pages, or music notes on my painted manuscript scores. That would break the silence: destroy today, yesterday, tomorrow; destroy the aloneness I feel in front of a piece of paper that allows me to talk inwardly, while also speaking to someone else.

Perhaps I am groping in the dark, in the light – trying to fill, or contend, with the void – my void.