When and where did I meet her for the first time? I believe it was some years ago. I don’t remember the season, but it was at a close friend’s home in Kamakura. We were talking partly in Japanese, partly in English. At that time, I had the impression that she was young, but not a girl; gentle, but not timid; reserved, but what she was saying was clear. And I felt some personal flavor which is not usual, in her way of thinking, or her way of feeling, or in both. She was Li-lan.

Her name suits her personality. Repeated “L” sounds beautiful; rather sharp “i” is followed by a relaxed bright “an”. Therefore, we should write Li-lan in the alphabet because the beautiful sounds will be lost if written in katakana* and pronounced “Ri-ran”. Rather, it should be written in Chinese characters . The culture of Chinese characters is going down in this country (Japan). I, myself, am in the lower end of this downward slope. According to Chinese customs, very well known in old Japan — Li — is used as a metaphor for a highly cultured and learned woman. Lan — silver — is a color often used in Chinese painting. The name Li-lan thus expresses well the person.

Some years later I went to New York. I came to know her in her studio, as well as in the environment in which se was brought up. We became good friends. She was born of parents – – one, Chinese artist, and the other, an American woman. She left home to live independently at an early age, and intended to become an artist. She went through the years of the 60’s as a young woman.

The 60’s were the period of “Sturm und Drang” of post war America. Young people were particularly adventurous, energetic. There was the rebellion against middle-class traditions: politically (civil rights movement, anti-war movement); artistically (Beat generation, Pop Art); socially (sexual revolution and hippies). In the process of going through that stormy period she became acquainted with Japan through Japanese artists in New York, particularly through Masuo Ikeda. In other words, she became acquainted with both the counter culture in America, and the other culture of the East, at the same time.

Since a few years ago, Li-lan has been producing large paintings in oil, open notebooks, white paper with nails irregularly arranged on it. I like her paintings and recognize her in them: thin, clear lines; delicately undulating surface; subdued colors; play between light and shadow; firm sense of presence of objects; the flavor of humor generated by arrangement of nails; seemingly cold, balanced space which yet conveys a certain warmth. For me, the impression of the person and that of the painting worked in opposite directions. As far as my impression of the person is concerned, it proceeded from soft, gentle surface to the discovery of the hard core. While my impression of the paintings went from cold, quiet order at first sight, towards a warm touch of skin.

It seems to me that New York City is much too complicated in order to like it, or in order to hate it. I lived there for two years. I have not investigated or studied its society. Instead, I lived it — I saw what I wanted to see, ate what I wanted to eat, and met people I wanted to meet — be they black or white, be they young or old, be they scholars or artists. And I wondered what New York looks like from inside. What taste would this world bear for someone who is born in that city — born and brought up in that city? That is something that Li-lan can tell us. Because she is sufficiently inside to know it, and sufficiently outside to talk about it. I got the idea to persuade her to use pen and paper for a while instead of brush and canvas.

In her writing, Li-lan looks back to the past, talks about herself and at the same time, New York. Even when the subjects concerned deal with Japan or Mexico, there is a world not of an American in general, but of a New Yorker. Everywhere in her writing, I recognize a trait of placing work in the center of life and self; of defining by herself how to limit the area of contacts with other people; the possibility to be ironic about herself. And, in connection with that, having a certain sense of humor, and perhaps the potentiality, if not actuality, of thinking that she, herself, is aware of everything that happens in her time and in the world. I like these characteristics, and am convinced that it is not only myself who sees it, but also a great number of the Japanese audience.

I admire Li-lan. Perhaps that’s why we became friends. Or rather, on the contrary, because we became friends, I admire her. Or both. My opinion of her may not be objective, but I believe that there is something more important than objective opinion between heaven and earth.

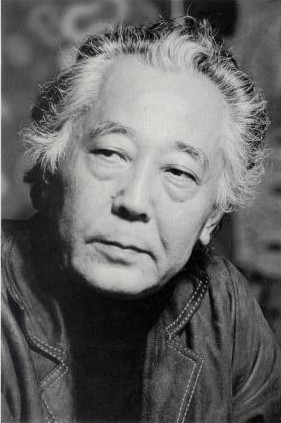

Shūichi Katō (加藤 周) was a Japanese critic and author best known for his works on literature and culture.