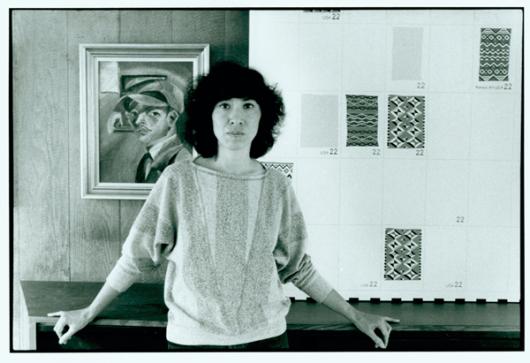

Li-lan in front of a painting by her father, Yun Gee, and one of her works at her Springs home.

In 1980, as a grown woman and mature artist, Li-lan visited the tiny rural village in China that 59 years before, her father, Yun Gee, a leader in early 20th Century avant-garde American art, had left as a 15 year-old to emigrate to San Francisco.

The experience, which she said, “was like a dream,” had a profound effect on her, one that she still cannot articulate even after eight years.

“It came about quite accidentally after a friend talked me into going on this artists’ tour of China,” said the artist, who goes by a single name, and whose works, along with those of her father, will be shown at the Art Gallery on the Southampton Campus of Long Island University starting tomorrow.

“I hadn’t planned to go looking for my roots or anything like that,” she said during an interview in her Springs house-and-studio. (She also has a loft on Canal Street.) “But once I signed up for the tour, I figured I might as well arrange to visit his village, which is in the unopened part of China. The Government cooperated, gave me permission and even provided me with a guide who could speak that particular dialect.”

Much to her surprise, Li-lan discovered that not only did the villagers remember her father – “He had sent money to them in the 40’s via China Relief,” she said – but also that his relatives who now live in the family house had put the postcards he had sent them announcing his gallery shows in the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s in a picture frame and hung it in the main room. The community is called Gee Village and it is in the Province of Kwangtung.

“They didn’t know he had died – in 1963 – but since he always told them he would come back some day,” she said, “they just shrugged and said, ‘So you came instead.’ It was all very Chinese.”

And being “very Chinese” was something quite foreign to her, for although she saw her father every week after her parents were divorced when she was 2 years old, essentially she was raised by her mother, Helen Gee, and American of European extraction.

“He’d occasionally talk with nostalgia about China, about his home and the lichee nuts that grew behind the house,” Li-lan said, “and once he tried to teach me Chinese writing, but he had turned to the West as an artist and, perhaps, culturally. Why, given the bohemian life he’d lead in Paris and Greenwich Village, I couldn’t believe he came from this tiny rural village.”

In fact, as a child, Li-lan had little contact with other Asians. Growing up in Manhattan, but not in Chinatown, she was often the only Asian in her classes. It was only after she graduated from the High School of Performing Arts, and, changing her interests from acting to art, took a job at the Takashimaya department store to support herself as an artist that she became even the least bit interested in the East.

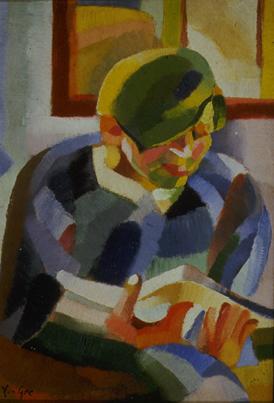

Yun Gee, A Woman Reading

Yun Gee, A Woman Reading

“I had very complex feelings about being Chinese,” she said. “And over the years, though I resolved some of them, especially after I married Masuo” – Masuo Ikeda, a Japanese printmaker, from whom she is now divorced – “and began spending time in Japan with him, some confusion still remained; perhaps, remains.

“That overwhelming trip to China and my father’s village, which I wrote about and illustrated with my own photographs for a Japanese magazine, resolved some of those issues; opened me up even more as a person.”

While she may have had problems dealing with her ethnic identity, she has experienced few difficulties with following her father’s professional footsteps. (She also shares her father’s talent for writing and has published books in Japan.)

“I remember seeing him in his studio, with brushes in hand, during the early years,” she said. “It never occurred to me that what he was doing was painting, even though he used to give me paper and paints and pastels to play with. So I must have been unconsciously influenced by the so-called ‘artist’s life style’. It must have entered into my decision to become an artist, but I can’t tell you exactly why the choice was made.”

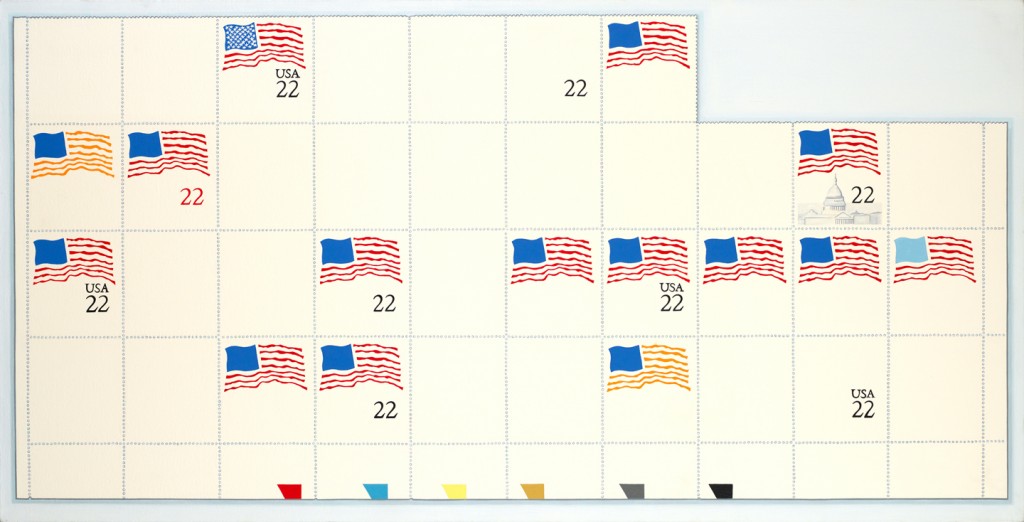

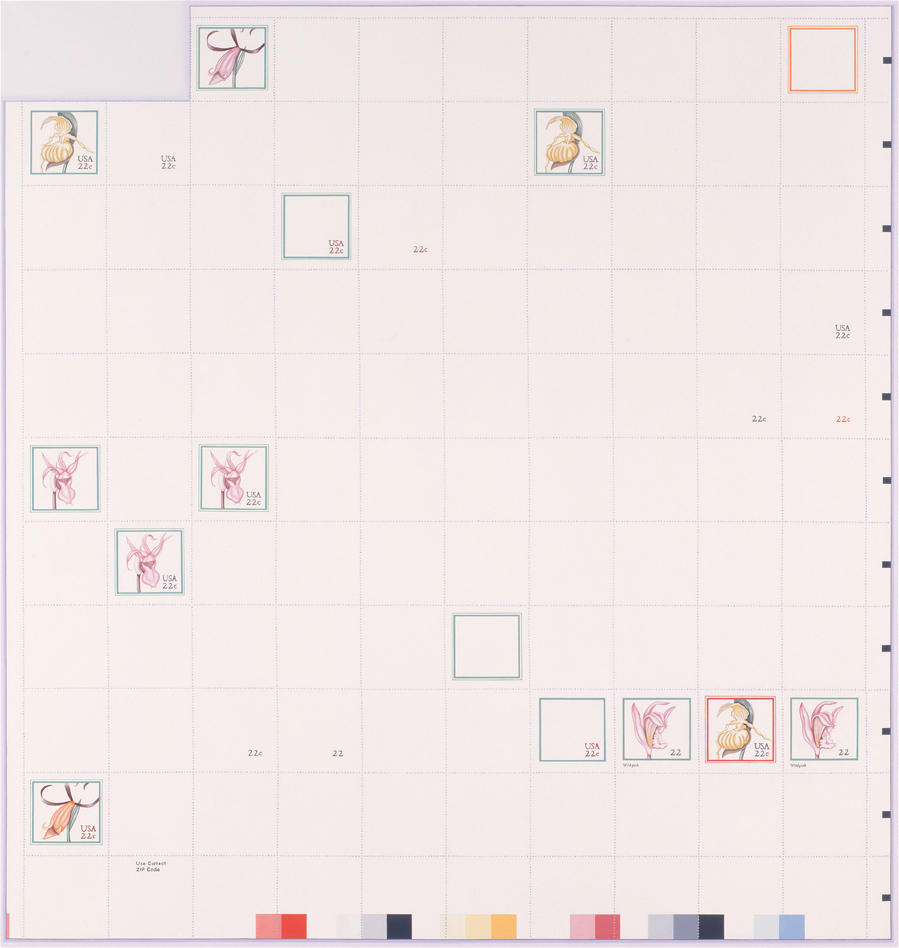

Thirty-Seven 22’s – 1987

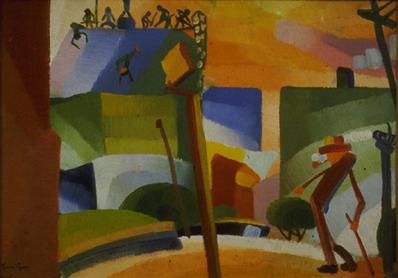

Art historians generally agree that Yun Gee’s contribution to the modern art that emerged from the social realism of the Great Depression era was major, in both the United States and Paris, where he spent much of the 1930’s. From 1926, when he had his first solo exhibition at the precocious age of 20, through the mid-1940’s, when for all intents and purposes his output ceased, he was at the forefront of the modernist movement.

Although his name is a footnote in the art history books and his paintings in the permanent collections of such institutions as the Whitney Museum of American art and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, his work generally has been forgotten, except for isolated exhibitions like the one that the William Benton Museum of the University of Connecticut organized and toured as a major traveling exhibition in 1979.

Yun Gee, San Francisco Street Scene with Construction Workers

“I want people to be aware of his work; I want him to get his due,” said Li-lan, explaining why, despite the dangers inherent in exposing herself to the inevitable comparisons, she “never hesitated for a minute” about joining in the Southampton show, “Yun Gee and Li-lan: Paintings by a Father and Daughter.”

A successful artist who had her first show in 1969, Li-lan never before had exhibited with him. The idea for the show stemmed from a realization by the gallery director, Roy Nicholson, that the two artists were related.

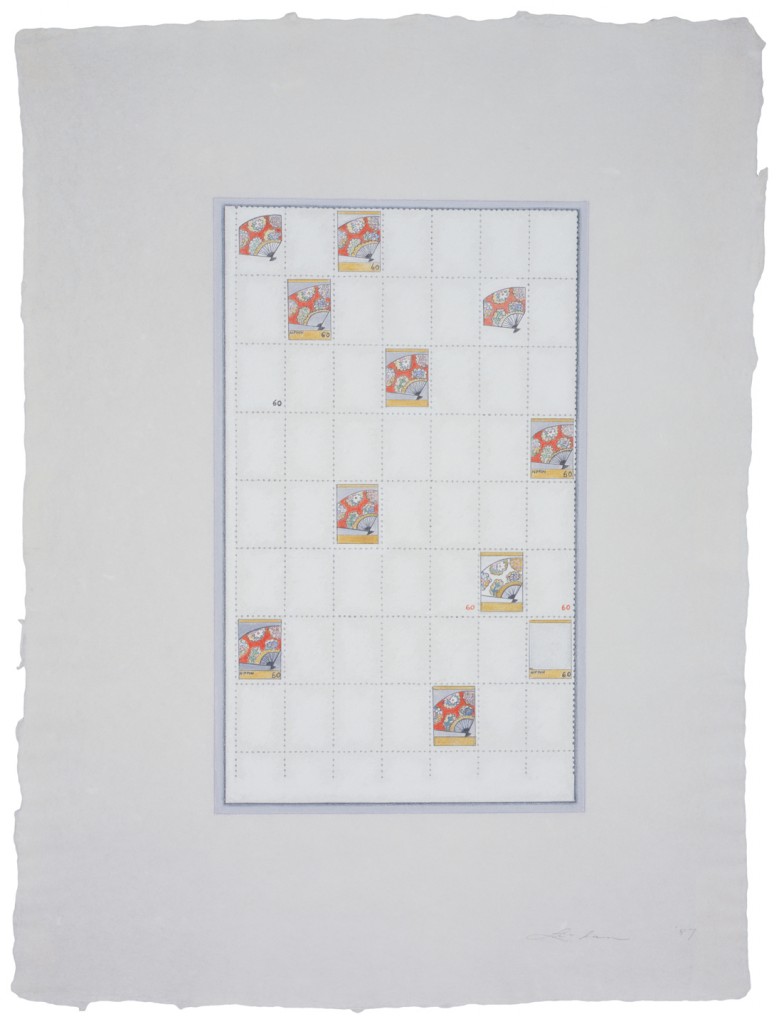

Nippon 60 Yen -1987

“I’d long wanted to do a show of Li-lan’s work, ” he said. “And I was familiar with Yun Gee’s. But I never put the two together, until someone mentioned they were father and daughter and then it became obvious. Would the family connection produce a connection in art as well? I see the contrasts, but I also see the similarities.”

At first glance, they share little in style. Yun Gee’s innovative approach was Cubist in nature, bordering on the abstract at times; Li-lan, on the other hand, is almost a minimalist, preoccupied by lines and open space. Currently, she is painting a series with a postage stamp motif.

“Abstractions don’t suit my temperament at all,” she said. “I’m too neat and precise a person to paint that way.”

Wild Pink: USA 22c – 1987

She welcomes the opportunity to compare her work, which critics have often found Asian in tone with its quiet, serene contemplation, with Yun Gee’s exuberant, energetic canvases, which show traces of his background in his use of color and brushstrokes.

“Seeing them side by side in a gallery environment . . . should give me some insights into questions I’ve long held,” she said. “So I’ll gain something from this experience just for myself.”

Barbara Delatiner is a retired freelance writer. She contributed regularly to the Long Island section of The New York Times.

For additional information on Yun Gee, please visit his website at www.yungee.com